By Ryan Maloney, assistant women's volleyball coach

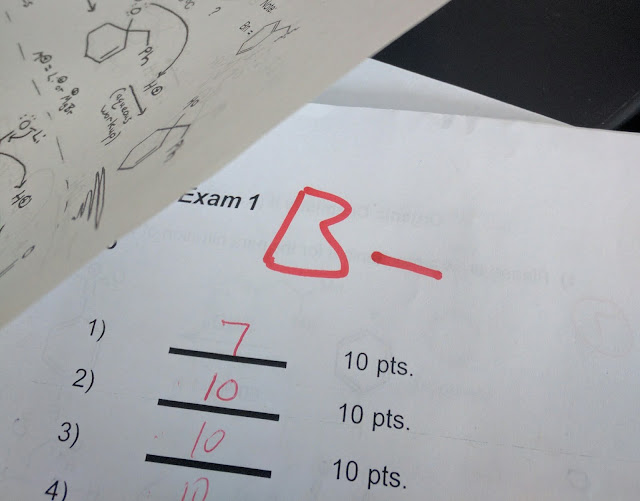

I recently got a text message from a former athlete who's in graduate school. She's having a hard time because she got a "B-minus" in one of her classes.

Stop for a second and consider how absurd that sounds.

But it makes more sense when you find out she's only allowed to drop below a "B" once. Now, for the next two years, she can't get below that in any of her classes.

There's one major benefit to this system: it promotes rigor and accountability in academics. This graduate school can, in theory, guarantee that it consistently churns out high-quality professionals. The system is also very, very convenient.

But there's two enormous drawbacks:

Anxiety -- A degree of anxiety is helpful to learning, pushing us towards our potential. But too much is devastating, and all too often students end up caring only about what grade they get, while the joy of learning is stripped away. "Is this going to be on the test?"

Grades are meaningless -- On my resume it says I, "graduated with a bachelor's degree in exercise science," and, "graduated Magna Cum Laude." So what? What does that mean? What classes did I take? What did I learn in those classes? How hard did I work? How is any employer supposed to know what that means?

Not only that, but grades have inflated over time. In 1983 at four-year public universities, the average GPA was below a 2.8; it's now a 3.1, and continues rising. Another wrench thrown into the system.

Most professors are fully aware of these faults -- grading is typically the least-favorite part of their jobs. I know first-hand how much easier it is to give an 'A' than to deal with students' anxious complaints about a 'B'. But one English professor I spoke with last year, Dr. Theodore Steinberg, had an ingenious solution to that problem:

Maloney: I remember you saying in class that if you didn't have to give grades you wouldn't.

Steinberg: Oh, yeah (laughs).

RM: Can you explain why?

Steinberg: I love teaching. I even love reading the (student) papers. But giving grades drove me crazy, because to reduce everything that a person has done over the course of 15 weeks to a single letter-grade didn't strike me as legitimate. How do you know you're right? And what does it even mean to be right?

RM: You, the teacher being right?

Steinberg: Yeah. I was teaching a composition course in one of my first years at Fredonia. There were two students who stand out in my mind. One was a young man who came into the class as a decent writer, about a 'B' level and he didn't put forth very much effort in the class. Then there was a young woman who couldn't put a sentence together at the beginning of the semester, just a terrible writer. But she worked like the devil over the course of the semester. By the end of the semester she was writing at maybe a 'C' or 'C+' level. What grades do I give them? Do I give a B and a C+? But that doesn't tell you much. If you were an employer which one would you want to hire?

RM: The one who worked harder?

Steinberg: Well, I think you can make an argument either way, but it's not that clear. So it just drove me crazy. What grades do I give? And what do those grades mean? How does anyone who looks at a grade that I give know what I think it means?

RM: I remember sometimes you wouldn't even give a grade.

Steinberg: I always had anxiety about giving grades, so I changed what I was doing. If a paper were below a certain level, I wouldn't give it a grade, but I would give it back with lots of comments. If you didn't get a grade you had to rewrite it. Almost always when students would re-write papers they would be significantly better. And I was then free to give better grades, I think the students were learning from the experience, and I stopped having anxiety about grading.